By David Pring-Mill

Media distribution influences creation, according to content creators. Different release strategies might complement or detract from content. Streaming services have the option to drop all episodes of a series at once or to sporadically pace out the release in a way that mirrors a traditional TV release.

Advanced awareness of the release strategy could conceivably affect storytelling techniques, as well as the types of stories that are being told.

Creative and Marketing Effects

The simultaneous release of all episodes in a season means that different viewers will be in different places throughout the narrative journey and that limits the nature of “water cooler” conversations. Some series might take time to win over audiences and a gradual release might allow any episode or series-specific cultural conversations to build off one another.

The absence of commercial breaks on streaming services also influences storytelling. An episode on traditional TV needs to dramatically build suspense before cutting to a commercial. Audiences might perceive that as unnatural. For storytellers, it could be creatively burdensome. Or it could be perceived more optimistically. Commercial breaks might offer an advantage by essentially resetting the audience’s attention and energy.

Streaming services aren’t relying entirely on originals. They’re licensing material that was originally developed for traditional TV. Consumers are returning to that content, or experiencing it for the first time, in a different way — without commercial breaks, and with the ability to binge-watch.

The Costs

With a steep demand for commercially viable content and an increasing number of entrants in the streaming space, these deals are sometimes exorbitantly priced. In some instances, the costs of those deals could be justified.

After a bidding war, WarnerMedia’s latest streaming service, HBO Max, reportedly paid between US $500 and $550M for the US streaming rights to “South Park.”

Luke Watson, a former consultant to the WWE and the current strategy lead at entertainment collective Noise Nest, told Policy2050 that this deal was worthwhile. He said that the show evolved substantially from its initial seasons and became a mirror that reflects society. It resonates with a broad, non-partisan, multi-generational, audience across all class brackets, which is valuable for streaming.

What Purpose Is Being Served?

The bar is high. Media content is now ubiquitous and it’s constantly delivered to all types of devices and increasingly to mobile devices. It’s worth reevaluating what need or want is being served.

Entertainment has long been promoted as a cure to boredom. But things changed. People today aren’t bored. They’re overwhelmed.

In his recent Netflix stand-up special (which had the apropos title “End Times Fun”), comedian Marc Maron reminisces about what PalmPilots were and hypothesizes that most people would quickly find themselves wandering the streets, completely disoriented, if they ever lost their smartphones.

Maron does an impression of what waiting in a line looked like, prior to cellular technology and the internet. After shrugging his shoulders, standing with his arms crossed, and exhaling repeatedly in frustration, he remarks to the audience, “Do you feel all that space I created? That used to be around us all the time! There was all of this space, lots of mental space! I mean, you had to wait to check for your messages at the end of an entire day!”

How does creativity change when you’re creating for a world that is missing “all that space”?

Content might have less depth. Or it might have more.

Targeting Different Demographics

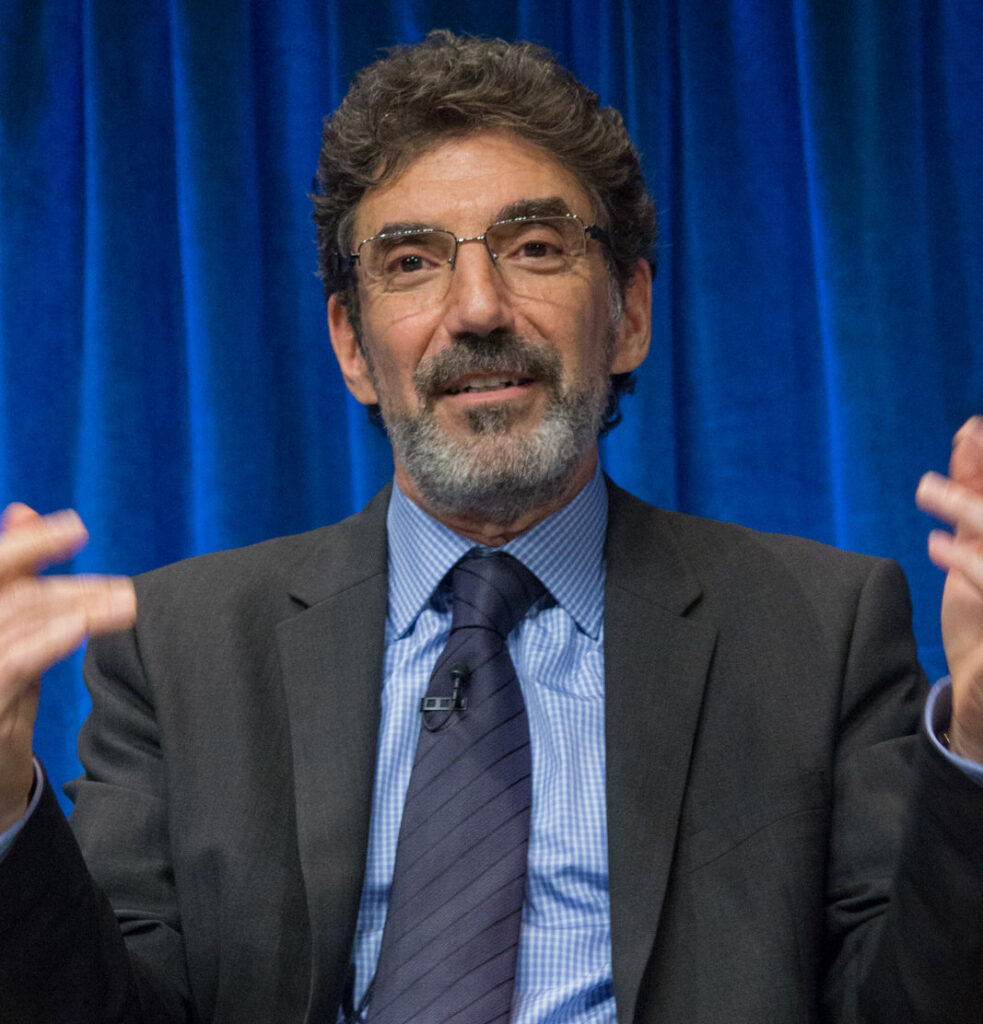

Chuck Lorre is one of the most successful television creators. When asked by Variety about the approach he’s undertaken with regards to his Netflix series “The Kominsky Method,” Lorre explained that he begins with the idea and decides whether it’s worth all the stress and fear of artistic creation. If it is, distribution becomes a secondary consideration. It’s all about connecting material with the right audience.

Lorre said that the TV network business still seems to be driven by demographics, whereas the streaming environment is driven by subscriptions. “So how old you are is irrelevant,” he said. “Are you there or not, is all that matters.”

The rate at which different demographics consume content may also prove to be relevant.

George Lopez, SVP of Operations at The Switch, works for a tech company that provides seamless live video streaming solutions to clients across media and entertainment. The end result often looks like a sharp and vivid sports game but the work is highly technical and requires support for various IP transport protocols.

He told Policy2050 that media companies often target young people because they have more disposable cash. He added that he’s 58-years-old and is more inclined to watch something like “The Kominsky Method” over a ten week period.

And this issue raises another question for the streaming services: “Can you be all things to all people? I think that’s a challenge they’re going to have to fight.”

Lopez said that the content on Amazon Prime Video often strikes him as cleaner, fresher, and more relevant, whereas Netflix content seems to reflect a higher degree of development, investment, and precision. “They’re purposely and actively looking for that home run they’re trying to hit with the amount of work and the amount of money they put into the content,” he said.

A Difference in Exposition and Pacing

Many of Chuck Lorre’s successful network shows were filmed in front of a live studio audience. Without one, the pacing changes and stories can find more natural rhythms. When commercials are removed, the average network TV show clocks in at 21 minutes per episode, which Lorre compares to a haiku or limerick.

Although constraints sometimes inspire creativity, Lorre feels that the relationship with the audience is fragile in network TV. “The commercials are this obstacle to maintaining a relationship with the audience,” he remarked.

Individual episodes often try to provide a sense of closure and they begin with the assumption that the audience has limited knowledge of ongoing storylines. Streaming is very different.

“Nobody jumps into a binge environment in the middle,” said Lorre. “In network television, you never know whether the audience was there last week. In fact, even if the show is really successful, I’ve been told, I’ve never known this to be verified, but the audience turnover from week to week, even in a big hit show, is enormous. The ratings may be the same but the audience, the actual human beings who are watching the show, changes dramatically from week to week. And so you don’t have that continuity of storytelling.”

The Business Perspective

Although these are largely artistic considerations, they could have an indirect effect on large-scale media ventures and investments. If storytelling techniques or aesthetics don’t resonate with subscribers, they might cancel. Their commerce decisions are based on an ongoing relationship with the media brand and it’s a conspicuous, identifiable transaction on their credit cards each month. It’s not obscured by a cable TV bundling.

The entertainment industry is very unique. The product is an experience. It’s digital, cultural, and often ephemeral. If you change the way that entertainment is consumed, you’re changing the product itself. Increasingly constrained attention spans or “attention economics” also affects the nature of entertainment products.

This is part of an ongoing series of articles about major disruptions in the technology, media, and telecom sector. You can read the other, related articles in Quick Insights and check the Whitepapers section for periodic, in-depth analyses. Subscribe for updates here.